WORLD Channel

The Conversation Remix: For Our Girls

Special | 10m 25sVideo has Closed Captions

Exploring the stigmas Black girls face as they grow up within and outside their community.

FOR OUR GIRLS, a love letter from mothers to daughters, explores the stigmas Black girls face as they grow up within and outside their community. Through interviews, mothers share concerns with how they are shaping and impacting their daughters' independence. The film acknowledges the sacred, and at times, tense relationship that parent and child share as they face challenges and accept flaws.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding provided by the MacArthur Foundation.

WORLD Channel

The Conversation Remix: For Our Girls

Special | 10m 25sVideo has Closed Captions

FOR OUR GIRLS, a love letter from mothers to daughters, explores the stigmas Black girls face as they grow up within and outside their community. Through interviews, mothers share concerns with how they are shaping and impacting their daughters' independence. The film acknowledges the sacred, and at times, tense relationship that parent and child share as they face challenges and accept flaws.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch WORLD Channel

WORLD Channel is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Be Seen, Be Heard, Be Celebrated

Celebrate women – their history and present – in March with WORLD, appreciating the hard won battles for gender equality and recognizing how much more we all have to work toward.More from This Collection

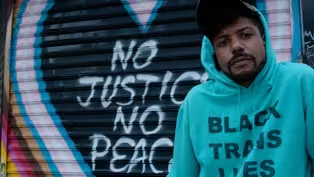

THE CONVERSATION REMIX explores the present catharsis we are living through, following the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Through three short, powerful character-driven films, we dive into how the current uprising is impacting communities, and how we can contribute to discussions about racial justice reform.

The Conversation Remix: Learning to Breathe

Video has Closed Captions

Black men reflect on their younger selves, sharing how their ideas of racism has changed. (9m 44s)

The Conversation Remix: Good White People

Video has Closed Captions

Unpacking how white people view and interact with race in America. (11m 26s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(waves crashing) ♪ NICOLE THOMPSON-ADAMS: It's almost like grief.

You know, it's that tsunami thing that comes rushing over you and then pulls back out like it wasn't there at all.

And trying to deal with one's daughter and her race and her experience... (sighs): I found challenging.

♪ ♪ ♪ I think I paid a lot more attention to my son and his sense of self than I did to her earlier.

I didn't recognize that she was getting lost.

Because she was articulate and smart, I left a lot out.

I wish I'd shored her up sooner.

We did everything to shore my son up as early as possible.

Make sure he got to the basketball so he could play with all the brown boys, make sure he did this, make sure he did that.

You know, put him in rites of passage.

We didn't do that for her.

We thought she was fine.

You know, in the media, they tell you your boy is endangered.

You feel like you're on safari and your son is a young lion and there's a poacher that is going to shoot and kill him.

Even though you might've experienced something, you don't take the same precaution with the daughter.

DENISE WRIGHT: I worry about the fact that somebody might be foolish out there, you run across somebody, you know, crazy out there, whatever not, and just because, you know, the way you are, you could be hurt that way.

I'll always have a little fear about that.

Nothing will ever change that, I don't guess.

(dogs barking, people shouting, arguing) GIRL: We were riding down this block and these white people start saying, "Get out of here, [bleep]."

You know, "Get out of my neighborhood, don't come to this neighborhood."

Then they start punching, hitting on her.

MONIFA BANDELE: Throughout our existence, in school, in the media, you know, we're constantly getting hit with these images of being hyper-sexualized and savage, uncivilized.

MAN: Do you forgive them?

No.

BANDELE: It's a way of beating us down in very much the same way we may get beat down in the street by the police or by, or by a racist mob.

♪ Police!

Open the door!

BANDELE: There's this whole confluence of violence that comes at us that goes unnoticed by the media, and goes unnoticed by other people, because it's not the way they typically see a violent attack.

MAN: Where you from, mama?

(indistinct talking) I find it difficult to figure out what's acceptable in the eyes of society for me to wear or how, how my body is viewed, if I can walk down the street without being catcalled all the time.

Because I just, I just want to go home.

I don't see why we have to have a full conversation about my body, and it's being, like, picked at by every guy on the corner of the street.

I remember as a seven-year-old or eight-year-old, my then-stepmother, she was, like, "You have to stay in the kitchen and watch me cook "and clean and do all this.

"But your brothers, because they're men, don't have to do that."

And I was, like, "Oh, that's awful.

"What are you talking about?

I don't want to do this."

And she was, like, "It's because you're a woman, "and especially because you're a Black woman, "the only way anyone will love you is if you can at least cook or clean."

It's just so deep, this pain, that we can't just settle.

It's not that I want stasis, but sometimes around these issues, like, I actually do, because it's a lot to always be deconstructing and working with.

♪ WOMAN: ♪ J-K-L-M-N-O-P Winner!

(laughter) (girl shouts playfully) BANDELE: I grew up where it did take a village to raise a child.

There was nothing I could go out my door and do that my mother would not find out about.

I am a proud helicopter mom.

My husband jokingly calls me Black Hawk Down, right?

Because I want to know everything that's happening, what's been said, how they're processing what a teacher has said to them, because these things eat away at them in ways that they don't know as children.

♪ (crowd chattering in background) This constant conundrum that we're in as mothers, as we go through life and we face these things and sometimes we let it roll off our backs, sometimes we challenge it.

We figure out these nuanced ways of moving.

But now here are our children, our girls-- you know, they're babies.

Sometimes I find myself just crying at night not knowing what to say or how to prepare them.

We want to build them up strong, but we also want to protect them at the same time.

(crowd cheering) When it's your daughter, you know, you...

There's a certain amount of pride in her growth and when she starts to mature and blossom.

You know, "Look at her, look at that."

Like a man when he sees his son, "Look at his muscles."

When you see your daughter and she's decided to do her hair... And to think that no one appreciated it.

I'm so ugly.

(woman gasps) (wailing) Baby girl!

WOMAN: So many, many years, we were told that only white people were beautiful.

You not going to cry.

You are a beautiful little girl and you are pretty.

You are the prettiest girl in your class.

It's like a new awareness among Black people that their own natural appearance, physical appearance is beautiful.

♪ THOMPSON-ADAMS: When you're little or even as a teenager, you need to be admired.

She went to an all-white school and kept telling me, "Oh, so-and-so is so beautiful, so-and-so is so beautiful."

And I had to constantly say to her, "Oh, but you're very beautiful," you know.

"You're very beautiful."

And she would hide it from me that she felt insecure, because, maybe because I was so hyper-secure, trying to show her how secure I was as a Black woman.

I'm really worried that she... no one sees her.

If I was, like, this smart young Black girl, where did I fit in this classroom?

That I would come home and my mom would be, like, "Who do you think you are?"

There's a groundedness that happens when you are seen, when you're heard, when you're loved.

I try so hard to, you know, address you as Janelle, but sometime it's going to slip.

But I don't be doing it to disrespect you.

It's just that, that's the way it comes out.

There are very few things that we need to really exist, you know, and have happiness.

And one of them is to be seen and to be heard and acknowledged.

♪ For a while, I couldn't understand where you was coming from as a parent.

As I grew older, I understood you only was doing the best that you could.

♪ GROUP: ♪ Happy birthday to you ♪ Happy birthday, dear Sammy ♪ Happy birthday... SAYEEDA MORENO: When I get upset, I think, "Am I going to be like my mom?"

That's, like, this overarching echo.

ZEMI MORENO-BILLINGSLEY: Yeah, but you can take from what she did that was bad and, like, do better than that, I feel like.

Yeah.

MORENO-BILLINGSLEY: We're all a little crazy.

(both laugh) Like... MORENO: We all have stuff, I know.

(indistinct chattering) BANDELE: I hear myself saying the same things that my mother said.

I see myself doing the same things that my mother did.

I wonder, will my children and my grandchildren also have to conduct their parenting the same way?

And will their parenting still have to be drastically different than their white counterparts?

You have to allow them to explore their genius and build on what we've done, because whatever is coming next, we're not going to be the architects of that.

It's going to be our girls.

♪ ♪

- News and Public Affairs

Top journalists deliver compelling original analysis of the hour's headlines.

- News and Public Affairs

FRONTLINE is investigative journalism that questions, explains and changes our world.

Support for PBS provided by:

Funding provided by the MacArthur Foundation.