Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 12m 8sVideo has Closed Captions

In the early 1490s, Leonardo da Vinci tackled his most ambitious work yet – The Last Supper.

Leonardo da Vinci started The Last Supper in the early 1490s. At the time, depictions of Christ sharing his final meal with his apostles were often sedate. Leonardo wanted to capture the drama of the emotional event. The mural would become one of his most well-known works, showcasing his gift for blending tones and colors, his mastery of light and shadow and his command of geometry.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate funding for LEONARDO da VINCI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and by...

Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 12m 8sVideo has Closed Captions

Leonardo da Vinci started The Last Supper in the early 1490s. At the time, depictions of Christ sharing his final meal with his apostles were often sedate. Leonardo wanted to capture the drama of the emotional event. The mural would become one of his most well-known works, showcasing his gift for blending tones and colors, his mastery of light and shadow and his command of geometry.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipIn the early 1490s, Il Moro had chosen a monastery to serve as a mausoleum for his family.

Home to an order of Dominican friars, the site featured a cloistered garden, quarters for the monks, a sacristy, and the recently completed Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

To adorn the south wall of the refectory, Sforza commissioned a fresco of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.

For the north end, Leonardo was to paint a scene suitable for the monks who dined there in silent contemplation-- the final meal Christ shared with his apostles before he was crucified-- the Last Supper.

It would be his most ambitious painting to date, featuring multiple figures engaged in a complex, dynamic narrative on a physical scale much larger than any of his previous works, including the abandoned "Adoration of the Magi."

It's a difficult subject for painters because it's a long, thin, wide picture, which is slightly difficult to organize, and you want some drama, or Leonardo wanted drama in it.

King: For the most part, Last Supper paintings would be very sedate scenes.

If you look at these paintings, Christ and the apostles ranged across the table mostly in silence, eating, maybe one or two talking together, and they're very placid scenes.

Borgo, speaking Italian: Narrator: He bought a Bible, a widely read Italian-language edition that had been translated from Latin two decades earlier.

The Gospels-- the books attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John-- offered varied but similar accounts of the evening on which Jesus gathered His 12 apostles and during dinner staggered them with a declaration-- "He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, the same shall betray me."

King: It's an incredibly emotional moment, where we have this charismatic religious leader with his band of brothers, and they're meeting in an occupied city whose authorities are plotting against them, and, of course, sitting in their midst is a traitor, the one who's going to betray the leader, and I think Leonardo was probably electrified by this story, and he was going to tell it in a very dramatic, theatrical way, a way in which no artist previously had thought about, let alone attempted.

Narrator: Leonardo began exploring how the disciples, roiled by Christ's words, would twist their limbs, wring their hands, and distort their faces.

Man as Leonardo: One who was drinking and has left the glass where it was and turned his head towards the speaker; another, weaving the fingers of his hands together, turns, frowning to his companion.

Kemp: For Leonardo, he had to understand how the body worked as a responsive machine.

What happens when Christ says, "One of you will betray me," with the brain and the nervous impulses and so on?

♪ He would see if he was looking, say, at a disciple who reacts to Christ's pronouncement by, say, throwing out their arms, that figure is expressing il concetto dell'anima, the purpose of the mind, purpose of the soul.

It's a way of expressing character and expressing emotion.

♪ [Door opens] Narrator: Leonardo erected scaffolding along the north end of the refectory and began his mural... ♪ first by coating the wall with a layer of plaster, then a binding agent, and on top of that, a primer of lead white.

♪ He pounded nails into the plaster for reference and used a ruler to draw construction lines and a stylus to etch grids.

♪ Using the incisions, he laid out the scene's ceiling and walls, constructing a space with realistic scale and depth and geometric harmony.

♪ One nail hole at the very center would serve as the point at which all perspective lines would converge.

♪ It was where he would paint the face of Christ.

♪ Man as Leonardo: Filippo, Simone, Matteo, Tome, Jacopo maggiore... Narrator: He made sketches in chalk and used a brush to paint outlines directly atop the plaster.

♪ Man as Leonardo: Pietro, Andrea, Bartolomeo.

♪ Marshall: The moment you lay down the first mark or first line, you're engaged in a process of evaluating every next step and understanding whether or not you have to make some major changes or some minor changes.

This is what's going on all the way through the process.

Narrator: Rather than follow the traditional technique for fresco in which pigments ground in water are painted on wet plaster and bind to the wall in a matter of hours, Leonardo used a mixture of oil and tempera that he'd concocted himself.

Bambach: This allowed him the luxury of painting during a long process of time so he was not limited to 8 hours a day and just one part of the design, and it also, very importantly, allowed him to create the transitions of tone and the transitions of light because you could not get the effect of light with fresco.

♪ Narrator: In layer upon layer, he applied the pigments that would, over time, bring the scene to life, often disregarding his initial outlines as the contours of his design evolved.

♪ For Christ's garments, he used vermillion, a pigment made from a brick-red mineral called cinnabar, and ultramarine, created by crushing lapis lazuli, a costly but brilliant blue metamorphic rock that could only be found in Afghanistan.

♪ "Often, he would not put down his brush from first light until nightfall, forgetting to eat and drink," wrote the novelist Matteo Bandello, who, as a boy, had watched as Leonardo toiled on the mural.

♪ On other days, he added little to the wall.

♪ [Birds chirping] Meanwhile, Sforza had grown impatient with Leonardo's unhurried pace and directed his secretary to draft a revised agreement that would impose a deadline on the artist.

♪ Within months, Leonardo was finished.

♪ The mural rose 15 feet from bottom to top and spanned 29 feet across the refectory's north wall.

♪ It showcased his gift for blending tones and colors, his mastery of light and shadow, and his command of geometry, which he wielded with great precision to bring harmony to a moment of chaos.

♪ Kemp: It's often said he's portraying a moment, that it's like a kind of flash photograph of what's going on.

It is in a way, but it's more complicated than that because if you look in the picture, the main thing is that Christ's saying is, "One of you will betray me."

Verdon: And they're all saying, "Is it I?"

"Is it I?"

"Is it I?"

And this central figure, totally focused on what's going to happen the next day and on the sign that he's giving of the offering of His body and blood, He gazes down in deep sadness.

He doesn't look at the apostles.

Kemp: And all the disciples react in a particular way apart from Judas, who's rigid and his tendons on his neck stick out because he's aware of what's going to happen.

♪ The announcement of betrayal then ripples out.

♪ Delieuvin, speaking French: ♪ ♪ King: This was the heart of the painting for him because it allowed him to show gesture and action and facial expression, the motions of the mind.

All of this 3, 4 seconds that happens at this table is unfolding before our eyes in this single image, and the brilliance of him being able to bring this off is truly astounding.

♪ Narrator: Leonardo da Vinci had magnificently rendered the gestures, both subtle and dramatic, that testified to the psychological states of his subjects, and he had resoundingly answered the question that he had asked himself many times before-- "Tell me if anything was ever done."

♪ Bambach: For him, painting was an entire philosophical meditation.

It is so much a process of thinking, of engaging, of feeling that was essential in his creative process, and, really, this is part of the reason that this painting has that transformative, transcendental aspect to it.

♪ When we go as viewers and look at it, we all fall into the same reverie.

♪

Early Works of Leonardo da Vinci

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 8m 40s | Leonardo da Vinci’s first commissions are a great way to explore his early painting techniques. (8m 40s)

How Leonardo da Vinci Created Narratives in His Paintings

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 6m 37s | Leonardo da Vinci paints The Virgin on the Rocks and the portrait Lady with an Ermine. (6m 37s)

Video has Closed Captions

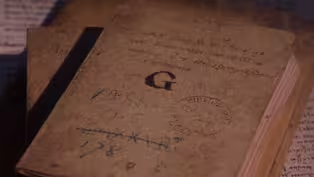

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 8m | Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks provide unique insight into his mind, knowledge and discoveries. (8m)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: 11/18/2024 | 1m 10s | Explore one of humankind’s most curious and innovative minds. (1m 10s)

The Vitruvian Man and Leonardo da Vinci's Anatomical Studies

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: 11/18/2024 | 8m 2s | Leonardo da Vinci studied anatomy to gain a deeper knowledge of how the body worked. (8m 2s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Corporate funding for LEONARDO da VINCI was provided by Bank of America. Major funding was provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and by The Better Angels Society and by...